„Der Film zeigt eindrucksvoll, wie das Schicksal der Holocaust-Überlebenden auch das Leben der zweiten Generation prägt und wie Geschichte in die Gegenwart hineinreicht.“

„Ein wunderbarer, zutiefst musikalischer und bewegender Film.“

„Wieder ein Holocaust-Film werden manche sagen, aber dieser ist so ganz anders.“

„Ein Dokumentarfilm mit großer Ruhe und Tiefe.“

„Ein vielschichtiger Film, der der Geschichte, der Kunst, vor allem aber den Menschen gerecht wird.“

„Der Film schafft einen unzerstörbaren Erinnerungsraum.“

"Ein Film, der Mut macht."

“Another Holocaust film, some will say, but this one is really different. Of course it is primarily a film about remembrance. But also a film which inspires courage touches the heart and shows the events from a different perspective. It tells events from a different perspective and most of all – it is cinematically extraordinary. “

Adrian Kutter, director of the Film Festival Biberach

Children instinctively notice when something remains unsaid. When questions regarding their parents’ past or about missing grandparents and relatives are answered vaguely or not at all. When the child realizes that the family roots are in another country. Growing older the child hears about the genocide of Jews during the Third Reich. He reads about it, sees horrible pictures and finds indications that his own family was affected by those events.

Salomon Korn (born 1943), former vice-president of the Central Council of Jews in Germany, compared the Holocaust with the film „Alien“: „One never sees anything and therefore in the child’s imagination it appears to be much more horrific than the reality already is“. Most children of survivors feel a responsibility to protect their parents and will therefore not ask questions. For the parents it is a balancing act to decide what, how much and when they should tell their children without frightening or overwhelming them.

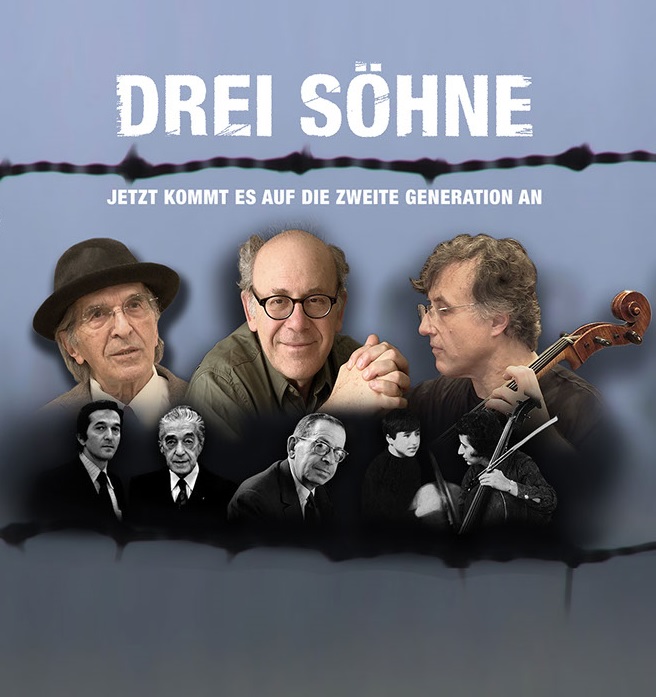

André Laks, professor of philosophy in Paris, Thomas Frankl, gallery owner in Vienna and Raphael Wallfisch, cellist from London, have something in common: each has a parent who survived Auschwitz. Their parents were artists: Anita Lasker-Wallfisch (cellist in the girls‘ orchestra in Auschwitz and later co-founder of the British Chamber Orchestra), the French/Polish composer Szymon Laks (conductor of the men’s orchestra in Auschwitz) and the painter Adolf Frankl (he painted the picture series „Visions from the Inferno“ after the liberation from Auschwitz). Their legacy for their sons was not only their history but also exceptional pieces of art: a ray of hope among the dark past. Each of the sons has found his own way to handle this legacy: ranging from not-being-able-to-let-go to open confrontation.

The film THREE SONS shows the history of the survivors through the eyes of the next generation. The second generation has to keep the memories alive when the last eye witness has died. No easy task in a world in which civil wars and refugee crises abound.

At the same time the film pays homage to the wonderful, long forgotten music by André’s father, the composer Szymon Laks.

“Over the last years the trauma of the postwar generation, the so-called second generation, has become the subject of more discussions. I was not interested in the families of perpetrators but in the families of victims. The deep silence which was also present in the families of Shoah survivors surprised me – which was partly due to repression or partly the wish to protect their children from the horrors as long as possible.

The film documents the different approach which the next generation took to deal with their parent’s history and heritage. I tried a new way and used the art and music created by the survivors to find out more about the way their children are coping with the past. The arts allow for a more empathic access to individual fates. The trauma touches the next generation as well and the three sons provide different solutions how to cope with this sensitive and complex topic in the future.

I was touched by the strong impact which displacement and persecution had especially on artists: hopeful careers were destroyed, creativity died or was lost. Szymon Laks survived Auschwitz and fought his way back to life – but how frustrating it must have been for him that nobody was interested in his compositions anymore. Today his wonderful music can be heard again and is played at large festivals, but this is a late compensation which he himself was not able to experience before his death.

Today the refugee crisis is the dominant topic in the news and therefore the commemorative culture is taking a back seat. But this is dangerous because the precursors are the same: growing hatred of foreigners and the search for scapegoats. Dealing with the past could help making the same mistakes again and find strategies on how to address the situation of todays’ refugees. “

Birgit-Karin Weber

documentary D/A/F/GB 2017

FBW: “Rating particularly valuable” – justification of the jury

length: 87 minutes

FSK: ab 12 Jahre (Freigabe für Besondere Feiertage)

Sprache: Deutsch, Englisch, Französisch, Original mit dt. oder engl. Untertiteln

Buch/Regie: Birgit-Karin Weber

Kamera: Martin Schilling, Steve Enste, Birgit-Karin Weber

Schnitt: Henning Fromme, Simon Adam

Motion Graphics: Simon Adam, Moritz Weber

Sound Design: Alexander Sonntag

Produzentin: Stefanie Greb

Produktion: Greb + Neckermann Filmproduction

Musik: Szymon Laks

Mitwirkende: André Laks, Thomas Frankl, Raphael Wallfisch,Anita Lasker-Wallfisch, Teda Wellmer, Frank Harders-Wuthenow, Marcel Sztejnberg

Format: Full HD, DCP, Blu-ray

„Der Film zeigt eindrucksvoll, wie das Schicksal der Holocaust-Überlebenden auch das Leben der zweiten Generation prägt und wie Geschichte in die Gegenwart hineinreicht.“

„Ein wunderbarer, zutiefst musikalischer und bewegender Film.“

„Wieder ein Holocaust-Film werden manche sagen, aber dieser ist so ganz anders.“

„Ein Dokumentarfilm mit großer Ruhe und Tiefe.“

„Ein vielschichtiger Film, der der Geschichte, der Kunst, vor allem aber den Menschen gerecht wird.“

„Der Film schafft einen unzerstörbaren Erinnerungsraum.“

"Ein Film,

der Mut macht."

“Another Holocaust film, some will say, but this one is really different. Of course it is primarily a film about remembrance. But also a film which inspires courage touches the heart and shows the events from a different perspective. It tells events from a different perspective and most of all – it is cinematically extraordinary. “

Adrian Kutter, director of the Film Festival Biberach

Children instinctively notice when something remains unsaid. When questions regarding their parents’ past or about missing grandparents and relatives are answered vaguely or not at all. When the child realizes that the family roots are in another country. Growing older the child hears about the genocide of Jews during the Third Reich. He reads about it, sees horrible pictures and finds indications that his own family was affected by those events.

Salomon Korn (born 1943), former vice-president of the Central Council of Jews in Germany, compared the Holocaust with the film „Alien“: „One never sees anything and therefore in the child’s imagination it appears to be much more horrific than the reality already is“. Most children of survivors feel a responsibility to protect their parents and will therefore not ask questions. For the parents it is a balancing act to decide what, how much and when they should tell their children without frightening or overwhelming them.

André Laks, professor of philosophy in Paris, Thomas Frankl, gallery owner in Vienna and Raphael Wallfisch, cellist from London, have something in common: each has a parent who survived Auschwitz. Their parents were artists: Anita Lasker-Wallfisch (cellist in the girls‘ orchestra in Auschwitz and later co-founder of the British Chamber Orchestra), the French/Polish composer Szymon Laks (conductor of the men’s orchestra in Auschwitz) and the painter Adolf Frankl (he painted the picture series „Visions from the Inferno“ after the liberation from Auschwitz). Their legacy for their sons was not only their history but also exceptional pieces of art: a ray of hope among the dark past. Each of the sons has found his own way to handle this legacy: ranging from not-being-able-to-let-go to open confrontation.

The film THREE SONS shows the history of the survivors through the eyes of the next generation. The second generation has to keep the memories alive when the last eye witness has died. No easy task in a world in which civil wars and refugee crises abound.

At the same time the film pays homage to the wonderful, long forgotten music by André’s father, the composer Szymon Laks.

“Over the last years the trauma of the postwar generation, the so-called second generation, has become the subject of more discussions. I was not interested in the families of perpetrators but in the families of victims. The deep silence which was also present in the families of Shoah survivors surprised me – which was partly due to repression or partly the wish to protect their children from the horrors as long as possible.

The film documents the different approach which the next generation took to deal with their parent’s history and heritage. I tried a new way and used the art and music created by the survivors to find out more about the way their children are coping with the past. The arts allow for a more empathic access to individual fates. The trauma touches the next generation as well and the three sons provide different solutions how to cope with this sensitive and complex topic in the future.

I was touched by the strong impact which displacement and persecution had especially on artists: hopeful careers were destroyed, creativity died or was lost. Szymon Laks survived Auschwitz and fought his way back to life – but how frustrating it must have been for him that nobody was interested in his compositions anymore. Today his wonderful music can be heard again and is played at large festivals, but this is a late compensation which he himself was not able to experience before his death.

Today the refugee crisis is the dominant topic in the news and therefore the commemorative culture is taking a back seat. But this is dangerous because the precursors are the same: growing hatred of foreigners and the search for scapegoats. Dealing with the past could help making the same mistakes again and find strategies on how to address the situation of todays’ refugees. “

Birgit-Karin Weber

documentary D/A/F/GB 2017

FBW: “Rating particularly valuable” – justification of the jury

length: 87 minutes

FSK: ab 12 Jahre (Freigabe für Besondere Feiertage)

Sprache: Deutsch, Englisch, Französisch, Original mit dt. oder engl. Untertiteln

Buch/Regie: Birgit-Karin Weber

Kamera: Martin Schilling, Steve Enste, Birgit-Karin Weber

Schnitt: Henning Fromme, Simon Adam

Motion Graphics: Simon Adam, Moritz Weber

Sound Design: Alexander Sonntag

Produzentin: Stefanie Greb

Produktion: Greb + Neckermann Filmproduction

Musik: Szymon Laks

Mitwirkende: André Laks, Thomas Frankl, Raphael Wallfisch,Anita Lasker-Wallfisch, Teda Wellmer, Frank Harders-Wuthenow, Marcel Sztejnberg

Format: Full HD, DCP, Blu-ray

Trailer

Protagonists

“We never talked about it at home and I never asked questions. It was there without being really there. It was like an invisible background which was not tangible. There was my father’s history and there was mine. They were two separate worlds and he never tried to involve me in his world. For him it was in the past and he didn’t want me to be part of that world. What I inherited was not the need to remember but the need to forget.“

André was born 1950 in Paris and grew up as the only child of the composer Szymon Laks and his wife Paulina. He has a doctorate in Ancient Philosophy, taught at Princeton University and the Sorbonne in Paris among others, is married with three children and now rotates between Mexico City, Princeton and Paris. After the death of his father he organized the publication and translation of Szymon Laks’ Auschwitz experience „Musiques d’un autre monde“ (“The music of the concentration camps”). At the same time he made efforts keep his father’s compositions from being forgotten.

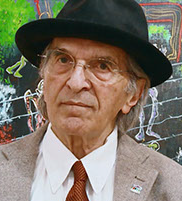

„In the late 1950s I saw that what my father painted was important and therefore have taken on not the duty but the task to help my father to exhibit his work. My younger brother couldn’t help very much and told me his reason for it: as a child he watched my father paint these sad and horrible pictures and was so shocked by that experience that he still suffers from it.”

Frankl was born 1934 in Bratislava. After a worry-free childhood in a well-to-do household he started to notice the repressions by the Nazis. His father Adolf Frankl was arrested in the fall of 1944 and deported to Auschwitz. Thomas and his sister were able to survive in hiding separated from their mother. After the liberation by the Red Army the family tried to restart their life in Bratislava but emigrated to Vienna in 1948. Frankl tried many different jobs and even spent time in the USA before founding a wholesale textile company with his wife in Munich in the 1970s. With the death of his father he spent more and more time organizing exhibitions for his paintings. Between 2006 and 2017 he showed the „Visionen aus dem Inferno“ (“Visions from the Inferno“) in his own gallery, located at the Judenplatz (“Jewish Square”) in Vienna.

“I think it would be a huge responsibility for parents who have had that past, to decide when it was appropriate to, if at all, to talk about it. Because it is something so horrific and so appalling that you don’t want to upset your child. I think my parents handled it amazingly well.”

Raphael Wallfisch born 1953 in London is the son of the cellist Anita Lasker-Wallfisch and the pianist Peter Wallfisch. He discovered his love for the cello early on and today is considered one of the leading cellists. His repertoire stretches from Johann Sebastian Bach to the present. Critics praise his recording of the complete works for cello and piano by Ludwig van Beethoven together with pianist John York and others. Over the last years he got more and more interested in music by persecuted Jewish artists and supports readings by his mother musically. He is married to a violinist and has three grown-up children who are also musicians or composers.

“We didn’t talk about it. Even if someone would have asked me if I had been in a concentration camp, where would I have started? How do you explain to a child that you have a tattoo on your forearm? I didn’t want my children to grow up with a hatred for Germany. If they want to hate Germans that is their decision but I don’t want to spread hatred. I find hatred the most abhorrent thing in the world. It is a poison that touches everybody around you and yourself as well. I spent half a century getting over my hatred for Germans but in the end I was successful.”

The Shoah witness Anita Lasker-Wallfisch was born in 1925 as the youngest of three daughters of a Jewish lawyer in Breslau. After the deportation and murder of her parents she and her sister first ended up in an orphanage but after a failed escape she was arrested and later deported to Auschwitz. She survived because she knew how to play the cello and managed to join the girls’ orchestra. After the war she emigrated to England and became co-founder of the famous English Chamber Orchestra. In 1996 after many years of silence she published her experiences from Auschwitz in the book “Inherit the truth”. Since this time Anita Lasker-Wallfisch travelled all over the world to talk about and explain her experiences to young people.

“The only way to understand what has happened is to try to identify with a real person and their family and then multiply that a million times. And then put yourself and your family in the same position and ask yourself why – and God help if there is a next time – why shouldn’t it happen to me as well?”

Speech given by Anita Lasker-Wallfisch on January 31st, 2018, in front of the German Bundestag during the memorial hour for the Holocaust victims:

https://www.bundestag.de/dokumente/textarchiv/2018/kw05-nachbericht-gedenkstunde/540648

“I got to know André Laks by chance. We have a common friend who is a colleague of his and a good friend from my youth. And then I found out about his tragic past and that his mother had expressed the wish that the music and memoirs of her husband should be heard in Germany. I totally agreed. One has to try because those were not numbers but human beings in the camps, people with talents, hopes, troubles and much else. That’s when I told him, I will try.”

In 1996 Teda Wellmer founded the culture initiative called “Frauen für Lemgo“ (“women for Lemgo”) which sponsors cultural events in their town. She met the son of the composer Szymon Laks by chance in the 1990s. Since then she promotes the musical and literary work of the artist. Thanks to Wellmer’s intervention the book by Laks “Musik in Auschwitz“ (“Music in Auschwitz”) was published in Germany in 1998 for the first time. . She also organized the first concert in Germany and the world premiere of Laks’s Symphonie für Streicher (“Symphony for strings”) in 1994. Her sister, the late actress Witta Pohl, read from Laks’s memoirs. Further events and concerts followed. For her efforts Teda Wellmer received numerous awards and also the “Bundesverdienstkreuz” (Federal Cross of Merit awarded by the Federal Republic of Germany).

http://www.nw.de/nachrichten/kultur/sterne_des_jahres/10514652_Frauen-fuer-Lemgo.html

“Music is alive and at its best it is something beautiful which appeals emotionally as well as spiritually. And it allows for a totally different way of coping which can help people talk about tragic events and at the same time associate it with something beautiful. Simply said, when people hear the cello sonata by Laks’ today, first they are enthusiastic because it is fantastic music – at the highest level and on par with anything else composed around the same time in the 1930s. And I manage to create an immediacy which helps people to approach the topic of the Holocaust which is in the background.”

Frank Harders-Wuthenow, born 1962 in Wiesbaden, studied music, philosophy and romance literature. After that he followed up with studies in music composition and theory. Since 1997 Harder works for the music publisher Boosey&Hawkes at their branch office in Berlin. At the same time he became co-founder of the label eda-records, which focuses on music by 20th century composers which were persecuted by Fascism and Leninism. In 2006 he was co-founder of the European Platform for Musicians persecuted during the Nazi period. He organized numerous publications, exhibitions and radio productions on the topic of “Verfemte Musik“ ( “Ostracized music”). He received various awards in Germany and Poland for his commitment.

https://www.rbb24.de/kultur/beitrag/2017/08/berliner-musiklabels-eda-records.html

“It was luck that I survived. In an internment camp I contracted an infectious disease and was therefore sent to a hospital in Paris. My aunt was able to get me out of there with the help of forged documents and hid me with farmers in the north of France for over two years. I planted a tree in Yad Vashem, Israel, in memory of Convoy No. 6 in which my father was deported to Auschwitz.“

The family of Marcel Sztejnberg was murdered during the Word War II by the Nazis. His father was on the same transport to Auschwitz (Convoy No. 6) as Szymon Laks. Marcel is the co-founder of the “Association Mémoires du convoi no.6“. The society published a list of all 928 men, women and children who were in the sixth of a total of 80 deportation trains leaving Pithiviers on July 17th, 1942, to Auschwitz. Marcel continues to do research and organizes events on the topic of deportation as well as taking care of survivors and their dependents’.

Team

Birgit-Karin Weber

“Auschwitz is for me like the dinosaurs in the museum: you believe you know the pictures and the history – but when you are there you are completely overwhelmed by the real scale. In Auschwitz your view travels to the horizon and the camp still continues beyond. You feel the humidity, the muddy ground, the cold, the inhospitable place and see the remains of buildings, pictures in the exhibition … and you start to get a sense of the unimaginable horrors people have suffered here.”

Birgit-Karin Weber, born 1962 in Wiesbaden, Germany, studied art history and architecture and first worked as an architect. In the late 1990s she succumbed to her love to film and for 12 years she worked for public television (ZED and 3sat). Next to short documentations and reports she discovered the portrait as her favorite format: what makes people tick, what fascinates them, how do they live, how do they cope with changes? Reality is often more thrilling than a movie. Since 2013 she works as a freelance director and produces documentaries for cinema and image films.

She is married, has three grown-up children and lives in Wiesbaden and in Schleswig-Holstein near the Danish border.

Filmografie (a selection)

2002 The inventor – portrait of Carlo Heller, builder of the sun dial (Der Erfinder – Porträt des Sonnenuhrbauers Carlo Heller), documentary, 3sat

2003 House sitter – Searching for the lost time (Der Haushüter – Auf der Suche nach der verlorenen Zeit), documentary, 3sat

2004 Trip to Trittin (Trip zu Trittin), film report

2005 Marionettes for Children (Marionetten für Straßenkinder), documentary about Nicaragua, Alle-Welt-Kino and ZDF

2010 No fear of G8 (Keine Angst vor G8), documentary

2011 Breaking down is not an option – when caring for the elderly (Zerbrechen geht nicht – wenn Pflege arm macht), film report, 3sat

2013 Aron and the Love for Opera (Aron und die Liebe zur Oper), documentary, 90 min., cinema premiere March 2014, Filmverleih Déjà-vu film UG Hamburg

Stefanie Greb

“A new perspective on the subject of the Holocaust, wonderful protagonists and the rediscovery of a very moving composer – all this convinced me to make a film with Birgit-Karin Weber about the fate of the second generation.”

Stefanie Greb, born 1973 in Frankfurt/Main, works as producer, director and author. During her studies as media designer for cinematography she founded Greb + Neckermann together with Arndt Neckermann in Wiesbaden. Besides many award-winning advertising productions and films for large corporations Stefanie Greb has spcialized on the production of top-level film and TV-productions with social and sociopolitical topics.

Filmografie (a selection)

2007 – „Truck Stop Grill“ – short film („Exceptionally Valuable“ rating by the German Film Rating Commission)

2008 „Be who you want to be“ – cinema spot (Lufthansa)

2010 „Für eine Handvoll Fische“ (For a handful of fish) – report (hr/SWR) „Zwischen Himmel und Erde“ (Between heaven and earth) – documentary (SWR)

(SWR) 2011 „Ein Pilot unter Hochspannung“ (A pilot under stress) – report (SWR)

2012 „Wir machen Profis“ (We make professionals) – cinema spot (Medienakademie Wiesbaden) „Comeback der Super Star“ – documentary (ZDF/3sat)

2013 „Auf der Straße zu Hause – Jung, obdachlos und wenig Hoffnung“ (at home on the street – young, homeless and little hope) – Reportage (SWR) „Ich hab’s geschafft! – Erfolgreiche Migrantinnen“ – short film (City of Wiesbaden)

2015 „Der 10.000-Meilen-Mann – Mit einem Handwerksgesellen um die Welt“ (The 10,000 miles man – around the world with a craftman apprentice) – Reportage (SWR) „Ich gehe alleine weiter!“ (I go on by myself) – cinema spot (Bärenherz)

2017 „Wir wollen Dich“ (We want you) – short film (City of Wiesbaden)

Greb + Neckermann

The business group Greb + Neckermann designs and realizes concepts for creative communication for international clients with high demands. In the center there are the film and post-production unit which works for established German TV channels and international corporations, e.g. ARD, ZDF, Deutsche Lufthansa, and Bosch. Successful creative concepts, communication solutions and visual media productions for business and industry range from documentary, reports to elaborate advertising productions.

The owners Stefanie Greb and Arndt Neckermann provide ideas and input for their creative environment as producers, authors and directors. Among others they have created the established media location FABRIKATION in Wiesbaden and founded the up-and-coming media academy Medienakademie Wiesbaden.

Henning Fromme

Media designer image and sound, specializes in film and video editing on the AVID Media Composer. He is responsible for digital image design and post-production within the FABRIKATION.

Martin Schilling

“Documentary and reports, industry films, image films and fast motion recordings show the range in which I work: always an open eye and fascinated by the focussed insights which we get with our work behind the camera: the work, the life and the people.”

Martin Schilling studied graphic design and media design in Mainz. Besides his love for typography and illustration he lives for his work behind the camera.

Since 1998 he is a freelance camera man: very adaptable, very optimistic, and always interested. He works passionately regardless if it is a large project of a small film.

The film music

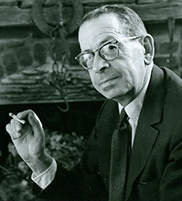

Szymon Laks

A picture in the feature section of the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung: an intelligent, friendly and lovable face. A face that invites you to read the article. It is about humanity, its loss and the great creative power of a composer who has experienced the unimaginable and yet was able to compose a largely cheerful music. A forgotten music that is now being rediscovered and played - a compensation, albeit a late one. In his opera "The Unexpected Swallow" ("L’Hirondell Inattendue". 1965), Laks recalls the power of music to unite people. How can someone after Auschwitz still believe in the good in people?

The preoccupation with the history of Szymon Laks comes automatically through the preoccupation with music. And then at the latest you can hear the work again with completely different ears: the breaks, the moments of deep sadness, despair, dying and then hope, playfulness and moments of total bliss. Laks is an enormously versatile composer and there is a corresponding passage for every mood of the film in his work.

Through his music, Szymon Laks is present as a person in the film.

When I came home as a free man friends and acquaintances asked the typical and somewhat intrusive question: “How was it possible for you to survive Auschwitz?” I usually answered: “ I don’t know hwo that happened. I think that if a few survivors returned there have to be some of those – and I was one of them. That is all. I have no other explanation for it.”

Only once I changed my answer when a woman asked with a demanding voice: “So many people were murdered and you survived. How did you manage that?” I blushed overcome with guilty feelings and answered hastily and admittedly somewhat ostentatious: “I am very sorry … I didn’t do this on purpose ….”.

Simon Laks studied mathematics in Vilnius before studying harmony, counterpoint and composition at the conservatory in Warsaw, his home town. He left Poland in 1926, 1927–29 studied at Paris conservatory under Pierre Vidal und Henri Rabaud , played the violin in cafés, on an ocean steamer, accompanied silent films and worked as a music teacher. Laks was key person in the association of young Polish musicians in Paris, got awards and performances of early works as: Blues symphonique, Wind Quintet, String Quartet No.2 (all lost now), Cello Sonata; in this time cooperation with the singer Tola Korian for whom he wrote numerous songs. 1941 Laks was arrested and interned in the camp of Pithiviers near Orléans, deported to Auschwitz II in July 1942. He survived the camp as a member and, later on, arranger and conductor of the camp orchestra, deportation to Dachau in October 1944. After the liberation he returned to Paris in spring 1945. Laks published memories of his time in the concentration camp as Musiques d’un autre monde in 1948 (revised Polish ed. 1979, English ed. 1989, French ed. 1991, German ed. 1998). He resumed composition, including film music under a pseudonym, while at the same time working on linguistic problems and a theory of subtitling films. Laks almost abandoned composition after the Six-Day War in 1967 and took up work as a translator and publicist. (Source: Boosey &Hawkes) In 1948 he wrote the book “Musique d’un autre Monde” about his Auschwitz experiences, which has since been translated into many languages.

Simon Laks about “die Rolle der Musik in den Konzentrationslagern “

Simon Laks was a member the group of Polish composers who lived in Paris in the interwar years and joined to form the Association des jeunes musiciens polonais (association of young Polish musicians). Though his talent was praised by early critics in Paris, he never achieved international fame. After the war, in which his musical works were partly destroyed, he composed little, keeping to his musical style which had developed under the influence of pre-war musical neo-classicism and thus abandoning the contemporary musical avant-garde. Though he still lived in the centre of the musical world, he no longer responded to current developments as he had done before. His style remained independent and was inspired by the École de Paris (School of Paris) with its respect for musical craftsmanship and the autonomy of the musicians.

The individual character of his music can be seen most clearly in the lyrical style of his vocal compositions which form a substantial part of his works. Following the war, Simon Laks resettled in Paris, maintaining, however, continual contact with Poland, particularly in the immediate post-war period. In 1949, his Balladfor piano was awarded 2nd prize at the Chopin competition. . In the same year, he received received 3rd prize at the competition for vocal settings of Adam Mickiewicz’s poetry for his songDe pures larmes me sont coulées…The following are among his works from the post-war period:

– Huit chants populaires juifs (1947)

– Poèmefor violin and orchestra (1954)

– Elégie pour les villages juifs (1961)

–String Quartets No.4(1962, Grand Prix de la Reine Elisabeth in 1965) and No.5 (1963)

– Concerto da Camera for piano and 9 brass instruments (1963, Grand Prix at the competition of Divonne les Bains in 1964)

– Symphonyfor strings (1964)

– Concertinofor reed trio (1965)

– Divertimentofor flute, violin, cello and piano (1966)

Laks’s works show numerous similarities with other composers from the Paris group, particularly Michael Spisak and Antonin Szalowski. The use of baroque and classical genres, in which traditional principles of form are combined with tonal harmony, reveals typical features of neo-classicism.

Laks’s instrumental works are characterized by a technical perfection that is typical of the Ecole de Paris, including formal construction, a sense of proportion, masterly polyphonic skills, rhythmic clarity and a simple and extremely clear texture. Cyclical forms such as sonata or suite are predominant, mostly for chamber ensembles. We also find typically Polish elements, as in the Suite polonaise for violin and piano (1935) or in theString Quartet No.3, as of course in the numerous folksong settings for choir (Echosde Pologne) and for Odeon orchestrea (orchestrion) (De chaumière en chaumière).

© Zofia Helman (translation: Andreas Goebel)

Der Komponist Simon Laks (1901-1983) von Frank Harders-Wuthenow (PDF)

Der Komponist Simon Laks (1901-1983) von Frank Harders-Wuthenow (MP3)

„SINFONIETTA“ (1936)

Kammersymphonie Berlin, Jürgen Bruns (conductor)

eda records, EDA 26 ©2006

„SUITE POLONAISE“ (1935)

Judith Ingolfsson (violin), Vladimir Stoupel (piano)

eda records, EDA 34 ©2010

„TROIS PIÈCES DE CONCERT“ (1932)

Judith Ingolfsson (violin), Vladimir Stoupel (piano)

eda records, EDA 34 ©2010

“SONATE POUR VILONCELLE ET PIANO” (1932)

Raphael Wallfisch (violoncello), John York (piano) Nimbus

NI 5862 ©2010

„STREICHQUARTETT NO. 3 SUR DES MOTIFS POPULAIRES POLONAIS” (1945)

Szymanowski Quartet Andrej Bielow (violin), Grzegorz Kotów (violin), Vladimir Mykytka (violin), Marcin Sieniawski (violoncello)

Avi-8553158 © 2009

„SYMPHONIE POUR CORDES“ (1964)

Warsaw Philharmonic Chamber Orchestra, Krzysztof Stowi´nski (conductor)

DUX 0737 © 2012

“DIALOGUE POUR DEUX VIOLONCELLES” (1964)

Stephan Heber (violoncello), Monique Bartels (violoncello)

FutureClassicsMusik © 2012

„HUIT CHANTS POPULAIRES JUIFS“ (1945)

NR. 7 “DI ALTE KASHE (L’ÉTERNEL PROBLÈME)“ Valéry Suty (soprano), Vladimir Stoupel (piano)

eda records, EDA 30 © 2007

„BLUES“

Marcel Worms (piano)

FutureClassicsMusik © 2012

„DIVERTIMENTO“ (1966)

Silvia Careddu (Flöte), Ib Hausmann (clarinet), Frank Forst (contrabass), Gernot Süßmuth (violin), Stefan Fehlandt (viola),

Hans-Jakob Eschenburg (violoncello), Frank-Immo Zichner (piano)

eda records, EDA 37 © 2013

OPÉRA „L’HIRONDELLE INATTENDUE“ (1965)

Libretto Henri Lemarchand Polish Radio Symphony Orchestra Warsaw, Lukasz Borowicz (conductor)

eda records, EDA 35 © 2011

“BALLADE HOMMAGE À CHOPIN (1949)

Vladimir Stoupel (piano)

eda records, EDA 34 ©2010

FILM MUSIC COMPOSED BY SZYMON LAKS (example)

Picture List

Adolf Frankl

The picture series “Visions from the inferno” by Adolf Frankl is under the patronage of the UN high commissioner for Human Rights.

“With my paintings I have created a memorial for all nations. I wish that no one, regardless of religion or political conviction, should ever experience such atrocities.”

Adolf Frankl was born 1903 in Preßburg (today Bratislava). After high school he studied at the Technischen Hochschule in Brünn (Austria) for several semesters while working as a caricature artist and illustrator of advertising posters at the same time. 1921 he joined his father in the family business for interior design. During Aryanization the company was expropriated in 1941 and the family suffered more and more discrimination. In September of 1944 the whole family was arrested and Frankl was deported to the camp Sered and later to Auschwitz. Frankls wife and children were able to survive by hiding separated from each other. After surviving the death march from Auschwitz to the concentration camp Althammer Adolf Frankl was liberated there in January 1945 by the Red Army. It took him three months to find his family in Bratislava. Adolf Frankl managed to reestablish his business but in 1949 it was nationalized by the communist regime. After this second expropriation the family emigrated to Vienna. There he concentrated solely on his artistic career. Later he followed his son Thomas to New York and in the 1960s also to Germany. Frankl painted until the late 1970s. He lived to see the first exhibitions before he died in 1983 in Vienna.

How I get my visions on the canvass:

„In a mixture of JOY and ANGER, I create areas of colour most of which unconsciously form a harmony – or the opposite. After some hours, I am forced to lie down because I feel so shattered. I sleep a little, smoke a cigarette and think about the past, about my youth and the women and also about the dreadful pictures of the camp. The ghosts creep slowly from the darkness. It gets to be unbearable. I flee to the coffee house; behind me I feel the unfinished picture ordering me back to work.”

Aus einem Vortrag von Prof. Dr. Willibald Sauerländer, Kunsthistoriker, München 1995

Der oft zitierte, heute vielleicht schon wieder halb vergessene Satz Adornos „Nach Auschwitz könne man kein Gedicht mehr schreiben“ – verweist auf eine tödliche Grenze aller vertrauten ästhetischen Erfahrung. Angesichts der millionenfachen fabrikmäßigen Tötung von Menschen … sind die Poesie wie die Kunst zum Schweigen verdammt. Kein Klagelied der Dichtung, so meinte Adorno, könne den Tod in den Gaskammern erreichen. …

Und damit bin ich bei den Bildern von Adolf Frankl und bei der Schwierigkeit, mich zu ihnen als professioneller Kunsthistoriker zu äußern …

Adolf Frankls Bilder und Zeichnungen, geschaffen, nachdem er dem Grauen von Auschwitz-Birkenau physisch entkommen war, aber in seinen Träumen und Erinnerungen weiter von ihm gepeinigt wurde, sind dagegen Innenansichten der Todesangst und der völligen, totalen Wehrlosigkeit. Man verharmlost sie bereits, wenn man etwa sagt: sie seien erschütternd. Nein, eigentlich machen sie nur sprachlos, lösen ein sprachloses Entsetzen aus. Was sie zeigen, das liegt so weit jenseits aller uns vertrauten Erfahrung, dass man sie mit unserer gewohnten Sprache gar nicht beschreiben kann ohne sie zu trivialisieren. Da wären wir dann doch wieder bei Adornos eingangs zitiertem Satz.

Lassen Sie mich trotzdem versuchen, umschreibend etwas über die spezifische Physiognomie dieser Bilder zu sagen … So sind die meisten Bilder Darstellungen ohne jede räumliche Distanz. Die kleinen, kraftlosen Figuren, die zerstörten, von der Angst zerfressenen Gesichter tauchen wie aus dem Unbestimmten, aus dem Nichts auf den Bildern auf. Sie sind weder nah noch fern – sondern nur auf eine traumatische Weise unverdrängbar anwesend … Um mehr zu verstehen, müssen wir Adolf Frankl selbst sprechen lassen: „Dann rauche ich und denke an die schrecklichen Bilder. Die Geister kriechen hervor aus der Finsternis – es wird unerträglich!“ Ich möchte auf eine zweite Besonderheit dieser Bilder aufmerksam machen. Diese Darstellungen erinnern an ein ungeheuerliches Geschehen, aber nie entfalten sie die Kraft zum Pathos.

Jene Pathosformeln, mit denen unsere Kunst – die Kunst, die nicht dem Trauma der Lager entstammt – seit den Griechen den schreienden, sportlichen, kämpfenden, heroischen Menschen dargestellt hatte, diese Pathosformeln sind auf den Bildern Adolf Frankls nirgends zu finden. Auf ihnen sieht man eine Gestik ganz anderer Art. Als deren Signatur mag man die kraftlos hängenden Arme bezeichnen, die Gebärde der Wehrlosen, der absoluten Opfer, die sich nicht einmal mehr aufbäumen können. Man sieht diese hängenden Arme überall: auf den Bildern von den Apellen, dem Prügeln, den medizinischen Versuchen, der Latrine. …

Lassen Sie mich auf eine dritte, vielleicht die empfindlichste Eigenart von Frankls Bildern eingehen: die Gesichter der Opfer. Es gibt viele Bilder, welche nichts als die Gesichter der Todgeweihten zeigen: bei der Deportation, beim Einwaggonieren, am Sonntag in der Baracke, beim Füttern, beim Hungern und Sterben. … Auf den Gesichtern, die Adolf Frankls Bilder zeigen, spiegeln sich keine Leidenschaften mehr. Die Augen treten aus ihren Höhlen, die Mimik zerfällt, alle scheinen transparent zum Tode hin. Solche Gesichter gibt es nicht in der Kunst außerhalb der Lager – nicht einmal bei Goya, bei Ensor oder Munch. Noch der Ausdruck des Wahnsinns ist ein aktiver Zustand gemessen an diesem Erlöschen der Pathognomik in der totalen Hoffnungslosigkeit. Adolf Frankl selbst hat von solchen Gesichtern gesprochen: „Diese Augen, ich kann es nicht vergessen, sein Gesicht war klein und voller Todesangst im Blick.“

Unter den Physiognomien, die man auf Adolf Frankls Bildern sieht, gibt es ein einziges Betongesicht, eine einzige Visage scheinbar heroischer Entschlossenheit: Es ist das Antlitz Adolf Eichmanns.

Aber die einzelnen Teile dieses Antlitzes werden in einer an den rudolfinischen Maler Arcimboldo erinnernden Weise von den abgemagerten Leichen aus den Lagern gebildet. Mund, Augen, Ohren, Nase. Unter der Schirmmütze mit dem Hoheitsadler und der Silberkordel starrt die Physiognomie der Endlösung hervor.

Betrachtet man die Maltechnik und die Farben der Bilder Adolf Frankls, so sind Anregungen durch den Wiener Expressionismus, die früheren Werke Oskar Kokoschkas unverkennbar. In diesen Wiener Bildern der Zeit um 1910 gärte eine ungeheuere Nervosität, ein antinaturalistisches Verlangen nach hypertrophem oder abgründigem Ausdruck. Aber bei Kokoschka und selbst bei dem noch exzessiveren Schiele blieb das alles an ästhetische Absichten gebunden. Auf Frankls Bildern ändern diese expressiven Techniken ihren Sinn. Die Malweise, das Arbeiten mit Pinsel und Spachtel, wirkt scheinbar inkohärent, ja chaotisch, aber gerade dadurch vermag sie es, das Unvorstellbare, die Auflösung aller Humanität und Sitte in der Welt des Lagers in Erinnerung zu rufen. Die Farben können laut sein – Rot, Gelb, Grün – ungeheuer dicht decken sie die Bilder zu. Sind sie harmonisch oder disharmonisch? Das sind ästhetische Fragen, die am Wesen dieser traumatischen visuellen Erinnerungen vorbeigehen. Eigenartig ist das Verhältnis von Farben, Figuren und Gesichtern. Sie kommen nicht zur Deckung. Die Farben überlagern, zerteilen, verschmutzen, verklecksen die todestransparenten Gesichter. Jegliche farbliche Ordnung würde eine Versöhnung stiften, die hier keinen Raum heben kann. Diesem dichten Chaos von Farben können die gepeinigten, geprügelten, am Stacheldraht verendenden Opfer nicht entrinnen. Keine der gewohnten ästhetischen Kategorien greift hier, sondern droht nur zu verklären, was in seiner ganzen Entsetzlichkeit sichtbar bleiben muss. …

So kann auch am Ende keines unserer Worte die Bilder Adolf Frankls erreichen, weil wir die Erfahrung des Lagers nicht teilen. Ich habe einiges, vielleicht schon zuviel gesagt. Denn eigentlich kann man zu diesen Bildern nur schweigen, schweigen in einer Scham, die uns – den anderen, den Nicht-Opfern – nie abgenommen werden wird.

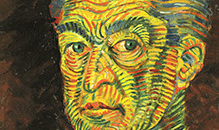

“Self-portrait” (around 1957) [„SELBSTBILDNIS“ Werknummer ÖH 217]

„My favorite picture by my father is his self-portrait which he painted in the style of van Gogh. I like it and only later on I noticed that wherever I am in relation to the picture, left or right, my fathers’ eyes follow me.” (Thomas Frankl)

“First roll call – the spirit oft he dead are looking on“ (around 1967) [„ERSTER APPELL – DIE GEISTER DER VERSTORBENEN SEHEN ZU“ (weg: Öl auf Leinwand) Werknummer ÖH 427]

“How the pictures affect me? Shocking, agonizing and I am left speechless. One knows pictures like these but when you see them like someone who was there the immediacy is greater as if you see it on TV. I try to picture it in my head and fail to find words for it.” (Comment by a gallery visitor)

“My beloved home town of Bratislava-Pressburg” (around 1959) [„MEINE GELIEBTE HEIMATSTADT BRATISLAVA-PRESSBURG“ Werknummer ÖH 002]

In this painting I present the tragic story of the Jewish population in my beloved home town during the Holocaust in combination with scenes from the bible. (Adolf Frankl)

„Visions from the inferno“ (around 1959) [„VISIONEN AUS DEM INFERNO“ Werknummer ÖH 219]

In this picture I wanted to depict the origin of mankind, our agony, our sorrow and our helplessness in the spiral of the mother.

In the camp I saw a dying mother who tried to protect her child with her dying breath. There were many emaciated bodies who died from weakness, strangulation, gas, being shot or suicide. (Adolf Frankl)

“Selection while the music is playing” (around 1967) [„SELEKTION BEI MUSIK“ Werknummer ÖH 109]

During the selection of the prisoners who were going to be killed the band was ordered to play happy music. (Adolf Frankl)

But the reaction was very diverse. Some people thought, there is music, it can’t be that bad, and for others the music helped them to image a normal world. And then there were the people who were terribly insulted – principally I can understand all of them. (Anita Lasker-Wallfisch)

“Evacuation from Birkenau – death march January 18th, 1945” (around 1965) [„EVAKUIERUNG VON BIRKENAU – TODESMARSCH 18. JANUAR 1945“ Werknummer ÖH 209]

On January 18th, 1945, the extermination camp Auschwitz-Birkenau was evacuated. Without any regard for our health condition and with insufficient clothing during the bitter cold around two thousand prisoners were sent on a march to Gleiwitz. Guards with machine guns and German Shepard dogs escorted us. If If you needed to follow nature’s call you had to run ahead and fall in line afterwards. Many prisoners didn’t survive the march. If someone lagged behind he was considered “disruptive” or “staller” and shot immediately. It was a miracle I survived this death march. Twenty sick prisoners, I among them, were segregated out and left behing with a guard. (Adolf Frankl)

„Death dance (behind the wire)“ (around 1965) [„TOTENTANZ (HINTER DRAHT)“ Werknummer ÖH 124]

Music had a different purpose in each concentration camp. In Auschwitz the music playing was not comparable to Theresienstadt. It was and medan to an end to organize camp life. The prisoners were marching in step to the music when leaving in the morning and returning in the evening. A cynical instrument by the camp headquarters in the truest sense of the word. (Frank Harders-Wuthenow)

“In the wire” (around 1951) [„IM STACHELDRAHT“ Werknummer ÖH 138]

The tormented, beaten victims dying in the barbed wire fence can’t escape this intense chaos of colors. None of the usual esthetics can be applied here because it would only transfigure what has to stay visible in it full horror. (Prof. Dr. Willibald Sauerländer, art historian)

“Selection in Birkenau” (around 1959) [ „SELEKTION IN BIRKENAU“ Werknummer ÖH 133]

In this picture you can see my father-in-law Oskar Nachmias in the second row far left with the green face. I day I came across him in the camp. Shortly before liberation he caught pneumonia. He was put in front of the barrack and water was poured over him. . He died shortly afterwards. (Adolf Frankl)

„Arrest of my family in Bratislava, September 28th, 1944” (1964) [„VERHAFTUNG MEINER FAMILIE IN BRATISLAVA, 28. SEPTEMBER 1944“ Werknummer AH 106a]

In this picture you see my wife, our children Thomas and Erika, my brother-in-law and myself. On September 28th, 1944 we were driven by German and Slovakian soldiers through the Michael gate to the gathering place. On the way a bystander shouted “Serves you right!” (Adolf Frankl)

„Sketches Sef-Portraits“ (1960-1970) [„SKIZZEN SELBSTPORTRAITS“ ]

Adolf Frankl was a driven man who could never escape Auschwitz, defined by it and still a person without feelings of revenge A man who wants to give a warning and a reminder to the next generations and in spite of it loved people and was a kind, modest lovable and shy person. Undemanding as he sat in his “Café Hawelka“ drawing his wonderful sketches which deserve much more recognition. In Adolf Frankl artist and human become one unit. (Prof. Carla Simalo-Loigner, Wien)

All images courtesy of Thomas Frankl and VG Bild-Kunst

The picture cycle “Visions from the Inferno” is under the patronage of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights